Working across scales to address flood risks in Cape Town

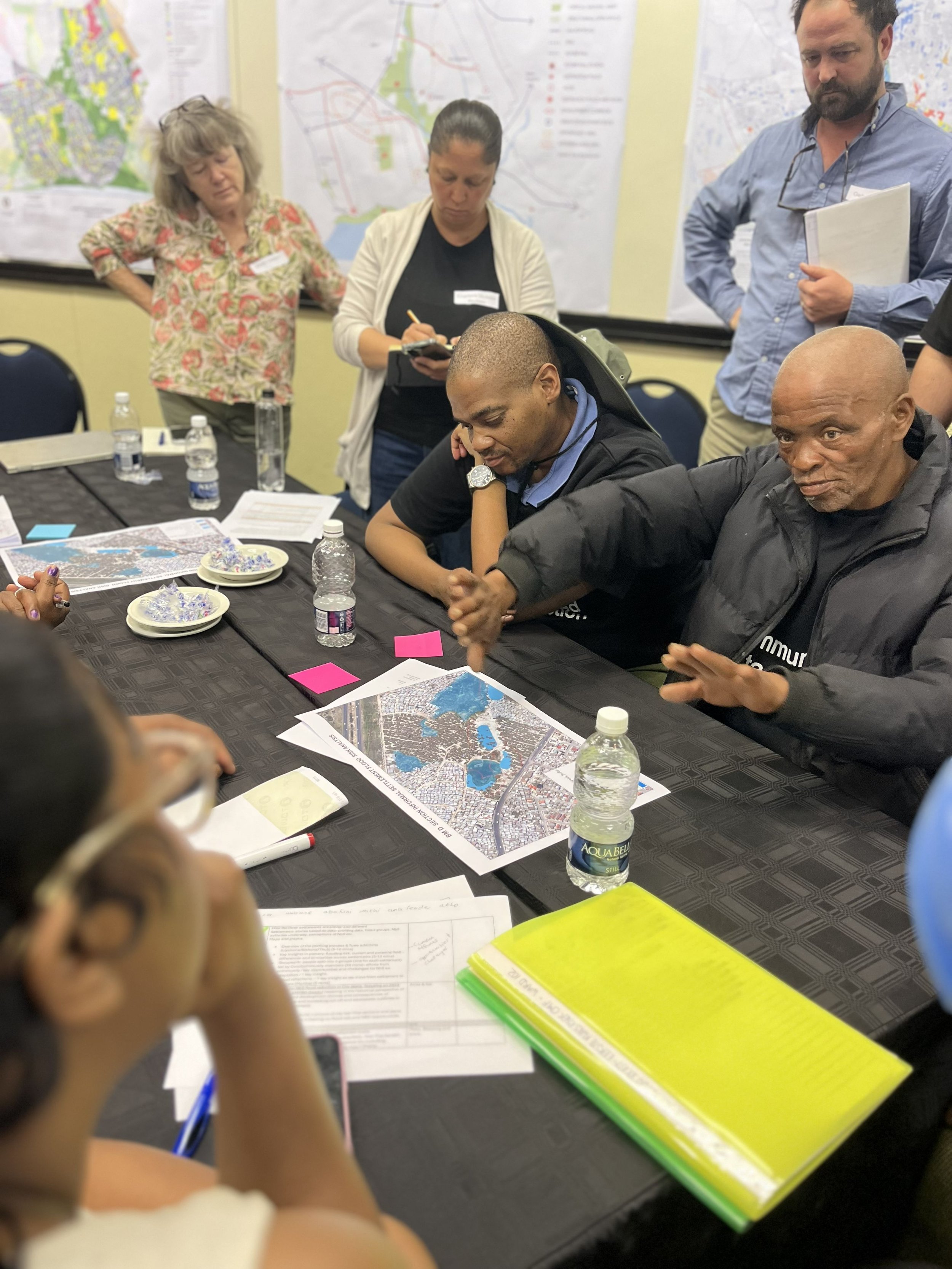

Members of the Tuwe Pamoja project team welcomed researchers, community leaders and government officials from Cape Town for a workshop on 30 October 2025 to explore the role of nature-based solutions for reducing flood risk in the city’s informal settlements of Khayelitsha.

Centred on the project theme of climate resilient development pathways (CRDPs), the workshop aimed to explore how flood risk reduction priorities of residents might align with those interventions taken or planned by various departments of the city government.

Narrowing their focus to three key sites within Khayelitsha, namely Msindweni, BM D section and BM C section, participants engaged with detailed maps of the settlements. These detailed structures, access routes, vegetated areas, water courses, wet areas that flood, and buffer zones.

“Our goal is to focus on nature-based solutions as a complement to other measures, such as grey and hard infrastructure interventions, to ensure as many people as possible are not living with the damaging impacts of flooding and poor water management,” said Anna Taylor, from the African Climate and Development Initiative (ACDI) at the University of Cape Town (UCT).

A member of the Tuwe Pamoja academic team in Cape Town, Taylor hosted the workshop with project partners from Slum Dwellers International (SDI) and the Community Organisation Resource Centre (CORC).

What are nature-based solutions

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are actions or interventions where people work or connect with nature to provide benefits for people (including themselves) and for plants and animals (biodiversity).

One example of a nature-based solution is creating and maintaining a community vegetable garden or soccer pitch. This green space can help rainwater soak into the ground, or act to restore the banks of a river by removing waste and invasive plants.

When these solutions are used to help people adapt to and reduce climate risks, like flooding and heat-waves, they are called nature-based solutions for climate adaptation, also known as ecosystem-based adaptation.

Drawing on their experiential and technical knowledge, the participants gathered to envision how nature-based solutions might be leveraged within these settlements and communities to make them more climate resilient.

For example, participants were asked to think about how site-specific interventions potentially fit into larger or longer development pathways of the Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain and Greater Blue Downs District and the Eerste-Kuils River catchment.

Place-based innovations

In her opening remarks, Taylor recognised that Cape Town rainfall is a known concern in places where stormwater and run-off from large built up areas accumulates, but underscored the risk of its impacts being further exacerbated by intensifying climate extremes and more land being converted from open space to formal and informal housing.

Profiling done by the Tuwe Pamoja team, led by CORC, revealed that residents in all three settlements had experienced flooding in the last 12 months. Other climate-related risks, such as fires, heavy rain, strong winds, extreme cold and heat were reported by residents of at least two sites over the past year.

“Our job is to think innovatively in a place-based way to see whether nature-based solutions can help create more opportunities for building resilience against these risks,” Taylor said.

Participants worked interactively to identify existing activities by households, community groups, businesses and local, provincial or national government that have a direct or indirect bearing on flooding in the sites, such as digging trenches, raising walkways using rubble and old tyres, and removing solid waste from drainage channels.

Participants also explored what measures qualify as nature-based solutions that reduce flood risk, and what opportunities exist to adapt interventions to be more nature-focused. Community leaders shared a desire to rehabilitate the local wetland and create safe, well-lit play spaces for children and places for adults to sit and enjoy the communal green space.

At the same time, participants highlighted a lack of tools, protective gear and understanding of government rules and regulations around what is allowable that hindered locally-led progress. The need for safe access routes in the rainy season, including for those using wheelchairs, to cross drainage channels and waterlogged areas was emphasised.

Participants worked in groups to discuss the potential for establishing participatory local planning forums, enhancing drainage infrastructure to move water into the Kuils River (getting ecological and engineered infrastructure working better together), and creating vegetated mutli-functional recreation spaces that can act as sponges.

Intersectionality and diverse expertise

An important aspect of the workshop was that it nurtured a collective respect for aspects of intersectionality, another of the Tuwe Pamoja project themes. Participants were encouraged to be cognisant of multiple factors that intersect to make each person’s experience of flood risk different, as well as what opportunities they have to intervene in reducing flooding impacts.

Instead of designing one-size-fits-all solutions, an intersectional approach calls for tailored strategies that address the unique challenges faced by individuals and social groups within settlements that live with multiple marginalised identities, ensuring that those most at risk are prioritised in building resilience.

Indeed, one of the strengths of the workshop was the diversity of experiences represented amongst the participants who had a mix of localised experiential, technical and scientific knowledge, many with decades of experience living and/or working in these locations.

One of the challenges of the workshop was adequately translating between English and isiXhosa to ensure that all participants felt included and well understood in the exchange of information and ideas. CORC members played a key role in translating inputs presented in isiXhosa into English.

One of the learnings from this process was that more time and resources need to be put into translating English presentations into isiXhosa to enhance accessibility. Also, group work needs ample time to enable translation both ways to be built into the brainstorming and co-design process.

Thinking about what is possible

Climate resilient development pathways (CRDPs) describe the accumulation of interventions over time – looking back and planning ahead – that shape how settlements grow and what risks and opportunities people living in those places experience. CRDPs seek to empower all to be part of adapting in ways that make a place safer for people, plants and animals alike as climate and other conditions change.

While climate change adaptation research involves significant forward thinking, not as much time is spent examining the past, says Taylor. “We have to look back at what shaped where we are now, and ask how that impacts where we go next.”

That work involves some shared imagination, where researchers, community leaders and government officials envision what it would take to enhance urban areas so they are attractive and resilient for the people who live in them, including those often overlooked because they do not formally own or rent the properties where they live, but have carved out a space and built a home with what they have.

It also involves sustaining communication amongst diverse and dynamic groups of people to negotiate trade-offs between different uses of space on sought after land, weighing up which parcels get used for public infrastructure, housing and ecological functions - and who protects and maintains them, using what resources.

Participants engaged enthusiastically in a series of group discussions amongst residents, researchers and government officials about what could be envisioned for the three settlements and what the next steps might be in taking these ideas forward.

Ideas included landscaping pathways with a mix of tyres, permeable cement blocks and water-loving grasses to make them safely passable when water was pooling for days after a rain event. Also, taking a landscape approach to upgrading drainage channels to connect water ponds and redesign water flows towards the N2 road reserve and the Kuils River.

Establishing a brick-making enterprise and a recycling hub to create skills development and livelihood opportunities linked to maintaining the area was also discussed. Getting recommendations from those with lived experiences of these spaces into city government plans for settlement upgrading was shared as a priority.

Building the capacity of local residents, who can’t afford the professional services of engineers and architects, to successfully navigate development application processes, including environmental and heritage authorisations, was also seen as important.

Engagement and communication

The newly established Eerste-Kuils River Catchment Management Forum was showcased as one opportunity for stakeholders from the wider area, including residents, local businesses and city officials, to keep engaging on a regular basis, including the opportunity to create sub-committees to focus on particular issues and getting things done together, in line with multiple objectives and formal procedures.

As commented by Hilton Scholtz, Director of the Road Infrastructure Management department at the City of Cape Town: “Our work involves roads and storm water management. We have a unit that deals with spaces of informality, or what I call ‘unplanned settlements’, where we want to explore how to bring the planning back in, so that circulation can take place [i.e. the safe movement of people, vehicles, water, waste, electricity, etc.]. That access is fundamental for all basic services,” Scholtz said.

“We hope to start an engagement with communities, and that’s why we are here. This workshop is very much community-led through the facilitation of UCT. Once you have that facilitation, it becomes non-political, non-partisan and supports the whole process so you can engage with the community in much more effective ways to find the right solutions.”